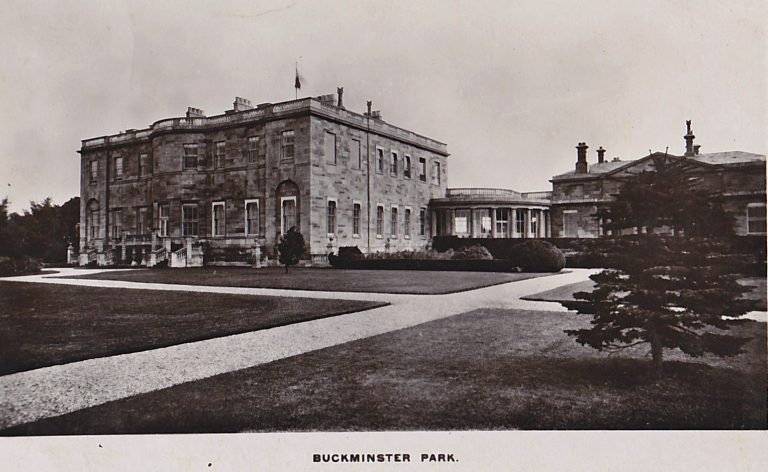

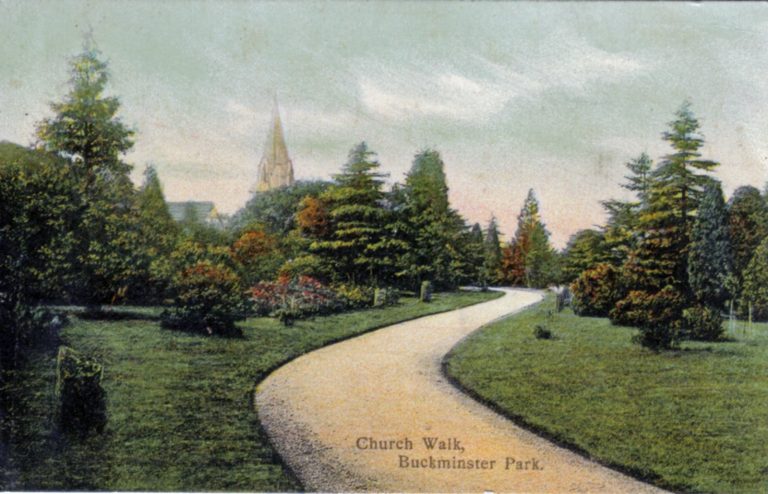

For most of its history Buckminster has been a small, agricultural village. Its character changed from the 1790s, when Sir William Manners decided to move to the village and built Buckminster Hall, a large Palladian-style property. This was demolished in 1951, following a fire and was replaced in 1965 by a Neo-Georgian house known as Buckminster Park.

- Walled Kitchen Garden

2.967 acres, including the frame-yard area. It is a skewed rectangle, oriented north/south.

Currently a small area of the northern part of the walled kitchen garden is used for vegetable growing. The rest is for equestrian use.

The southern walled kitchen garden is still an orchard.A modern glasshouse, built on the brickwork of the former vinery remains and still contains grapevines.

An interview was carried out in March 2015 with the son of Edward (Ted) Dunkley who was a foreman gardener and then head gardener during the first half of the 20th century. The transcript of this interview is shown in the report below, as are plans of the walled kitchen garden and frame yard, based on drawings produced by him.

OS Map 1904 showing location of walled kitchen garden

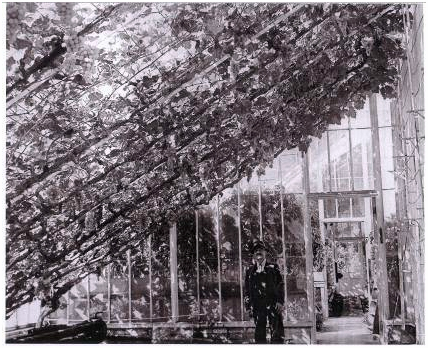

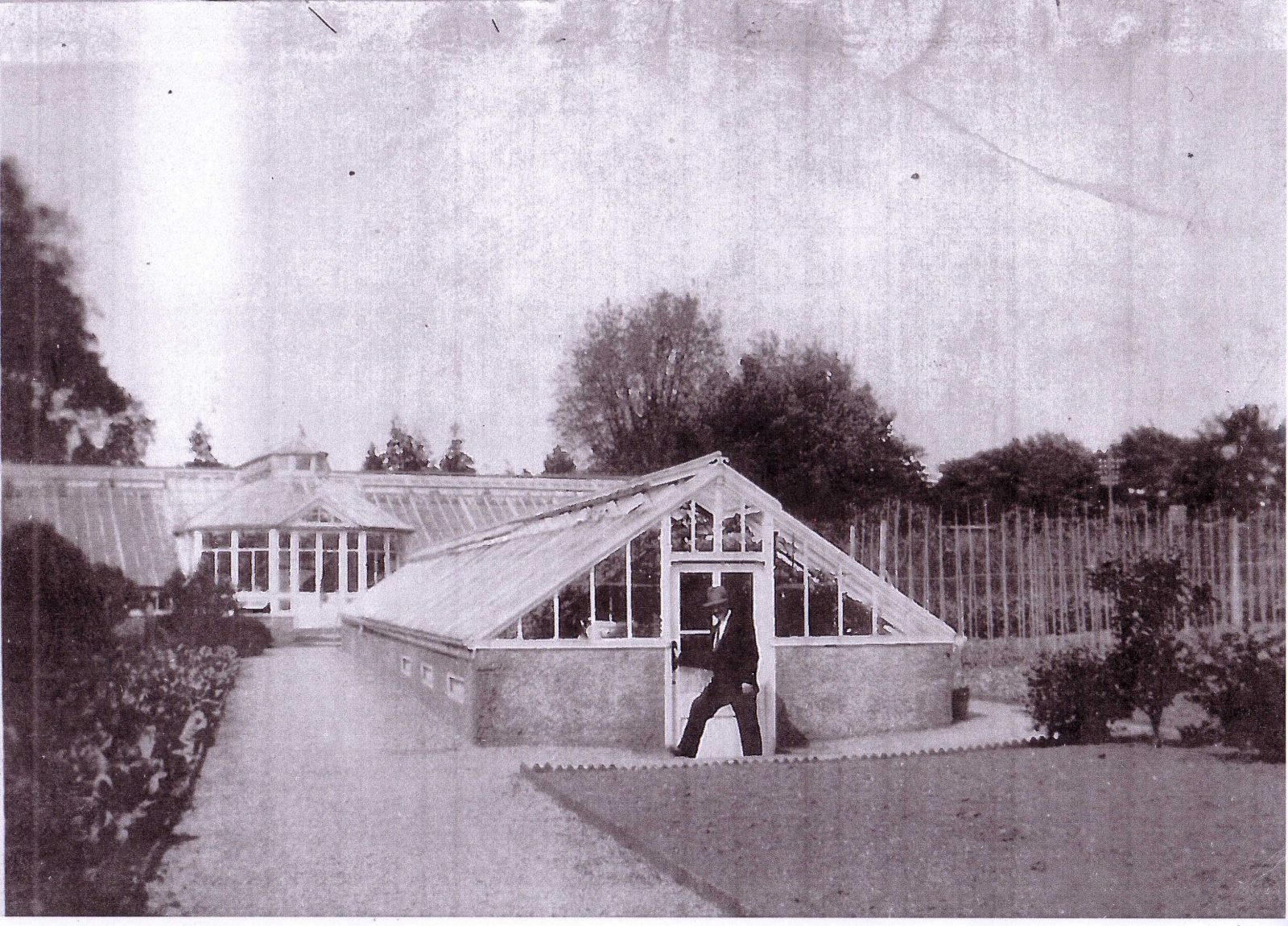

Ted Dunkley as foreman gardener in front of the entrance to the Forcing House. C.1912

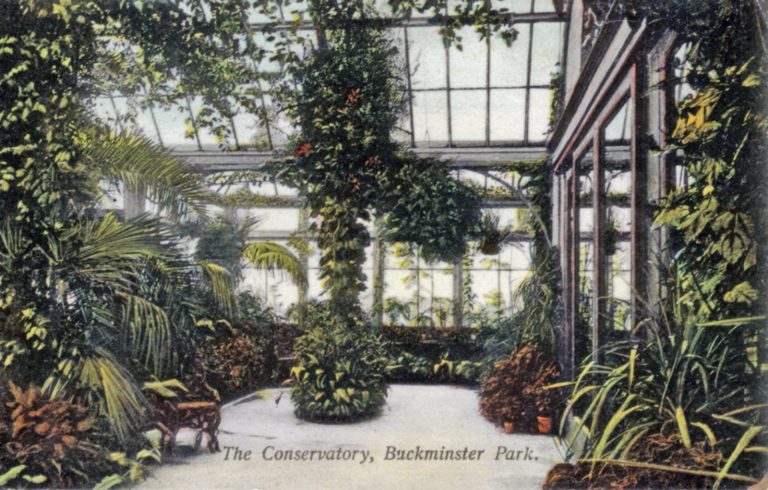

Range of glasshouses with conservatory in the centre and lean-to vineries to either side. (Shows design of conservatory). Ted Dunkley, head gardener, in the background. Photograph likely to have been taken on a Sunday with the “duty gardener” next to Ted and another gardener in his “Sunday Best” on the right. Date: 1920’s

Ted Dunkley in the Vinery – 1940’s

Ted Dunkley walking past the entrance to the sunken forcing house - 1940’s

Head Gardener’s Cottage Buckminster: Notes from Interview with Geoff Dunkley - 12 March 2015

Geoff Dunkley’s contact details were supplied to us by Richard Tollemache (the present owner of Buckminster Hall). Geoff’s father, Edward (Ted) Dunkley had worked at Buckminster as head gardener and we arranged to interview Geoff to talk about his father’s career. Geoff Dunkley is now in his mid-80’s but his memories of Buckminster are very vivid and extensive.

This is a transcript of the notes that were made at our meeting with him.

Ted Dunkley was one of eight children. The family lived in Market Harborough, where his father had a shop. Geoff described this as a “gardening shop”, presumably selling garden tools etc. Ted worked for his father when he left school but then got a job at Broughton Hall in Yorkshire and then at Nidd Hall, also in Yorkshire.

In 1909 Ted applied for the job of Foreman Gardener at Buckminster. He cycled down from Nidd to Buckminster. (This is 106 miles down the A1). He was offered the job, cycled back to Nidd to hand in his notice and then back to Buckminster to start work.

He lived in the bothy, where, according to notes written by Geoff, the bothy boys were looked after by a Miss Grice, who came in from the village to cook and clean. Geoff said that there were 14 gardeners before the First World War. Geoff supplied us with a photo of his father, taken c 1912, standing outside the forcing house – you can see prize chrysanthemums in pots behind him. (This photo is shown on the website data entry form)

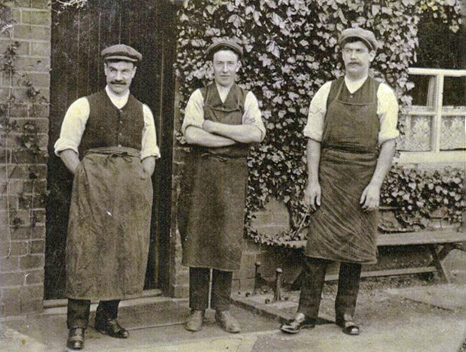

At the outbreak of the 1st World War, he and his two pals, Humphrey Rudkin and Tom Armstrong (a groom), enlisted in the Lincolnshire Regiment. They fought on the Somme and both Humphrey and Tom were killed during the war, with Ted as the only survivor. (See the photo of them below, standing in front of one of the back sheds). Geoff has published his father’s 1st World War memoirs – the book is called “Tommy being Tommy”

Ted returned to Buckminster and was made up to head gardener in 1927. He married Geoff’s mother, Margaret Annie Rayson, who was in service at the Hall. At this point, he earned £2 10s 0d per week with the head gardener’s house, free coal, free electricity and free fruit and vegetables supplied.

The estate was then owned by William Tollemache, 9th Earl of Dysart. Lily ponds and a new terrace were created at this time but were subsequently demolished. The family lived at Buckminster for six months of the year, the winter months, for hunting and shooting, as one might expect.

Geoff was born at Buckminster in 1929, in the head gardener’s house, which was one of the estate cottages – the first house on the left on the Sproxton Road. .

In 1935, Lord Dysart died and the estate was crippled with death duties. The walled kitchen garden was used (as far as we could gather) as a market garden, with the “frame yard” having plants and shrubs standing out for sale. Fruit, such as grapes, peaches, nectarines and plums was sold to a wholesaler in Covent Garden called T.J. Poupart (who still exist). In season, 10 boxes a day were collected by a man with a lorry, driven to Grantham station and sent to London by train. Geoff has marked on the plan of the walled kitchen garden the area that was used for packing the fruit.

By this time, the number of gardeners was significantly reduced. The bothies were no longer used as most of the younger gardeners had to finish.

During the 2nd World War, there were only two older men working in the gardens: an ex-convict (called Swinghurst) and “Old Bob”, who had learning difficulties. Geoff, as a teenager, used to work in the gardens during the summer holidays.

He told a story that his father had instructed him and Bob to pick fruit in the orchard area of the walled kitchen garden. Geoff decided that the quickest way for them to do this was for him to climb the trees and shake the fruit down! Bob would pick the fallen fruit. Needless to say, Ted was not pleased to discover this and dismissed them both (but he reinstated them the next day!).

Geoff recalled that, during the second summer, he got a job on a farm at 5/- a week more than his father was paying. So the Estate Office increased his pay to 10/- a week in order to keep him.

The Hall was visited by an official from the Ministry of Food who instructed that all the exotic flowers in the conservatory had to be removed and replaced with tomatoes, for local sale. Ted was allowed to keep his grape vines but was ordered to remove the peaches and nectarines. He was very reluctant to do this, as they had taken years to train and grow, so he ignored the instruction. A second Ministry of Food official visited in due course and said that they could be kept, provided that he was supplied with a hamper of fruit when he visited! Geoff said that he saw this happen. So the peaches and nectarines survived the War.

The Hall itself was used as a convalescent home for wounded soldiers and the produce was used for the patients.

The glasshouses were removed in the 1950’s and the area was used for equestrian purposes, as it is today.

Geoff said that his father loved his work and got on very well with the Dysarts and the Tollemaches.

By the time of his death in 1952, at the age of 66, he was still working, with a young girl aged about 19 and “Old Bob” to help him. Old Bob lived in one of the bothies, but became elderly and infirm and moved to live with his sister in Leicester. He died in the Leicester Workhouse (which, by then, was used an a old people’s home)

There were several other pieces of information and anecdotes that Geoff told us:

The area outside the walled kitchen garden (where the snowdrops now grow) was known as the Elysian Fields. He mentioned that there was a 40 foot deep well in this area, which had not been capped off. There was also a well in the area near the bothies. There were no ponds.

After the War, his father had a problem with fruit being stolen. He discovered that Swinghurst, the ex-convict, was the culprit. Swinghurst’s wife came into the garden during Ted’s lunchbreak and together they were stripping the trees and vines. Ted suspected what might be happening and asked Geoff to hang around and watch out. They were caught red-handed and Swinghurst was dismissed.

His father was responsible for growing flowers to decorate the Hall and the church, at Christmas.

Ted Dunkley, Humphrey Rudkin and Tom Armstrong

Ted Dunkley’s grave in the churchyard at Buckminster Plans of Walled Kitchen Garden and Frame Yard at Buckminster Hall, based on drawings by Geoff Dunkley, son of former Head Gardener

Plan of the Frame Yard at Buckminster Hall

Plan of the WKG at Buckminster Hall (North Section)

Plan of the WKG at Buckminster Hall (South Section) See our full research report on the Walled Kitchen Garden here:

Buckminster Hall, Buckminster

- Detailed Description

Two large terraces were constructed as part of Buckminster Hall between 1795 and 1820, known as Bull Row and Cow Row. These were let to tenants who worked across Sir William's estate in Leicestershire and Lincolnshire. Sir William's mother was Lady Louisa Talmash, who became the 7th Countess of Dysart in 1821, following the death of her brother. Sir William became the heir to the earldom, took the surname Talmash (later Tollemache) and the courtesy title Lord Huntingtower. His great grandson, the 9th earl of Dysart, who inherited in 1878, spent heavily on village improvements. These included the demolition of the Bull Row terrace and its replacement with higher-quality semi-detached family homes, the creation of reading rooms in 1886, which became Buckminster Institute in 1898 (the forerunner to the Village Hall), the restoration of St John the Baptist church and the building of a new village school.

- Photos

- References